Prompted by the release of season 2 of Girls on DVD and preparing to teach the show on a new module in Autumn, I thought I would put up a paper I gave earlier this Summer at the Television for Women conference at Warwick (15-17 May 2013). This was a paper which charted a small part of the vast discourse surrounding the show’s debut, and as it is a paper about the smart, thoughtful commentary by a range of diverse (largely female) voices I wanted to give a shoutout to the women of my twitter feed who have thought through, blogged and unpicked the show throughout its first two seasons and whose words informed this paper. I also wanted to highlight this post by Amanda Ann Klein, which links out to many of the key pieces and helped me think through this mountain of discourse.

The Prezi that accompanied this paper can be found here.

The show that launched a thousand blogs: The reception of Lena Dunham’s Girls

Television for Women Conference, 15-17 May 2013, University of Warwick

This is not a paper about Girls, rather it’s a paper about people talking about Girls. It is about a discourse, the commentary, the hype that swirled around the half-hour HBO show, created by then 25 year old Lena Dunham, about a group of upper middle class white women muddling through their early twenties in Brooklyn. This paper focuses on the pre-publicity and immediate reception of Girls in its initial week or so of broadcast – this was more than enough for 20m paper.

This is not a paper about Girls, rather it’s a paper about people talking about Girls. It is about a discourse, the commentary, the hype that swirled around the half-hour HBO show, created by then 25 year old Lena Dunham, about a group of upper middle class white women muddling through their early twenties in Brooklyn. This paper focuses on the pre-publicity and immediate reception of Girls in its initial week or so of broadcast – this was more than enough for 20m paper.

I want to position Girls as a catalyst for conversation. The show prompted many multi-faceted responses across a range of print, online and social media – which thought-through ideas around race, gender, class, bodies, sexuality, authorship, industry, distribution. This conversation highlighted culture’s ever present need to ‘worry’ about young – white – women’s bodies and voices, yet also showed how online cultural commentary opened up space for a diversity of womens voices. This discourse is intersectional, to use all the fancy words, and closing it down to one thing or another – just female authorship, just class, just race – ignores the complexity of the conversation and women’s place in culture. We are not singular!

So I would suggest that Girls + the insightful, engaged, critical, angry, funny talk – by journalists, academics, cultural critics and all – Girls + this conversation = is a thing. Though the many-voiced messiness made your head hurt at times, it is a prime example of how television is produced and made complex through this discourse. Am going to pull out a few of these key points in circulation, to map some conversations about Girls, but necessarily skipping briefly over complex events.

Context

Girls arrived in a particular cultural context, within the post-Bridesmaids 2011-12 US television season, where a wave of female–fronted sitcoms debuted – primarily chronicling white, heterosexual, twentysomething women who all looked a certain way: 2BG, Whitney, Bitch in Apt 23, New Girl. These were shows created by women – though often showrun by men and had writing rooms where women remained in the minority – thus conversations around gender, race, comedy and authorship were already primed.

Girls arrived via a carpet bomb of hype from HBO and was perhaps fatally overexposed from the get go. As well as traditional media HBO targeted the online cultural spaces frequented by it’s desired demographic of young tech-savvy, female, viewers. Girls was tied fast to its creator-writer-director-star Lena Dunham and her rarity as a 20-something star and showrunner with creative control – her authorship and distinctive ‘voice’ were repeated emphasised. Girls was inescapable, profiled on culture and lady blogs, television review sites, on public radio stations, in magazines and newspapers and billboards the size of buildings.

Critical praise for Girls and Dunham coalesced with the themes pushed by HBO: its ‘authenticity’, realism,verisimilitude. Girls’ ‘universality’ was aligned with Dunham’s freedom with her ‘imperfect’ body and the flawed nature of the women she created. TV critic Willa Paskin at Salon framed Girls as a ‘generational event’, whilst in a New York magazine cover story Emily Nussbaum argued the show was ‘like nothing else on tv’ celebrating it as ‘for us, by us’. But the question of who this ‘us’ began to be asked as Girls spread beyond this press first wave.

Girls had a cross-platform presence, supported by Lena Dunham’s strong social media profile, where she chronicled production via tweets and instagram. Trailers for the show circulated via youtube, and centralised Hannah’s claim that she could be the voice of her generation, well a voice of a generation. A phrase repeated in critical conversations about Dunham herself, beginning the blurring of Hannah and Dunham.

Significantly HBO made the Girls pilot available free on youtube, thus making it a piece of spreadable media – circulated widely across the internet, beyond the largely white, middle-class, North-East-based media world that had framed the initial conversation. New commentaries problematised the claim that Girls was ‘like nothing else on tv’, noting its much vaunted divergence from Hollywood femininity was limited to one ‘non-normative’ body, wrapped up in a safe white, upper-middle class, heterosexual world. This response opened up a range of conversations about what we wanted from our television representations of womanhood and who makes them.

Authorship and autobiography

Throughout the conversations around Girls, Lena Dunham’s status as auteur was intertwined with the questions over her closeness to her protagonist. Dunham suggested in the New York magazine profile that Girls was her least autobiographical project, although in a radio interview with NPR’s Terry Gross she claimed ‘I did write something that was super-specific to my experience’ and that ‘I really wrote the show from a gut-level place, and each character was a piece of me or based on someone close to me.’ The slippage between Dunham and Hannah was compounded by her previous videos and indie film Tiny Furniture, which mined similar territory to Girls and also starred herself. Alongside her precocious creativity, Dunham’s privileged background – her private school and Oberlin college education, her artist parents – formed a central part of her press profiles, and fed into the privilege critiques which I’ll pick up in bit. What else is there to write about a 25 year old who went virtually straight from college videos to ‘auteurship’?

Whilst the young, female, relationship-based nature of Girls could have marked the show as a delegitimized ‘feminine’ form, the focus on Dunham’s authorship and indie-film cred helped legitimize the show as part of HBO’s channel identity. Though Girls shared DNA with HBO’s low-profile quirky comedies of young(ish) male New Yorkers – Flight of the Conchords, How to Make it in America, Bored to Death – HBO’s hype escalated Girls to the cultural blockbuster level of a Boardwalk Empire or a Game of Thrones (though without their audiences). Thus Dunham was positioned within HBO’s discourses of quality ‘authorship’, Davids Chase and Simon, Larry Sanders, Scorsese etc, a boys club where her gender marked her the ‘diversity’ hire.

Yet her auteurship, her solo voice and achievement at landing an HBO series in her mid-twenties was problematised by the involvement of Judd Apatow, film comedy writer/director/producer /juggernaut. He became Dunham’s mentor after viewing Tiny Furniture and worked with her to develop and sell Girls to HBO, going on to executive produce and write for the series. Apatow was Dunham’s stepping stone, but also something of a millstone.

Privilege

Apatow’s role in Girls creation played into discussions of both Dunham’s privileged background – her access to him via the elite cultural circle she was born into – and the worldview/lifestyle of her characters. In part as a way for some observers to unpick her success and devalue her creative worth – ‘here’s how Girls really got made’. In part to question the ‘universality’ the early hype claimed for the series, the narrowness of Dunham’s storyworld.

As Girls exists within a world of privilege, these are young women making their way in New York – well Brooklyn – but with a parental safety net. The catalysing event of the series as a whole being Hannah’s parents withdrawl of this safety net. The blurring of authorship and autobiography / Dunham and Hannah – and perhaps a tonal problem in the pilot’s writing – fed into conversations around how much Girls was valorizing or satirising Hannah’s entitled worldview, displayed in the conversation with her parents that was the centerpiece of the widely circulated trailer.

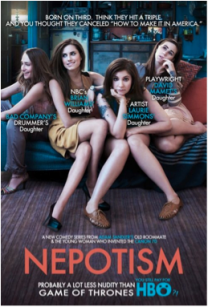

Here Girls stepped into a combination of ongoing cultural conversations: of privilege and ‘first world/white people problems’, of entitled Millennials and an anti-hipster mockery. Privilege fermented perhaps the most vitriolic of the show’s critiques and was where misogyny hid most plainly: with charges of nepotism highlighting the cast’s parental connections as daughters of the cultural elite – musicians, artists, playwrights, broadcasters. As daughters of privilege, it was inferred their success was owed to connections rather than talent, highlighted in a much circulated photoshopped poster.

Yet as others rightly pointed out, male showrunners’ family connections and privilege are never credited for their success – Buffy’s Joss Whedon comes from a long line of Hollywood writers, whilst Scrubs and Cougartown’s Bill Lawrence is an American blue-blood.

Yet this conversation made privilege visible – Dunham does come from a background and world that gave her access to film funding straight out of university, her parents Manhattan loft to shoot her first film in, access to Apatow, and a lifestyle that is more highly valued in television. In contrast a young black woman – Issa Rae – from a similar background, with a hit web series – Awkward Black Woman – and the mentorship of Grey’s Anatomy’s showrunner giant, Shonda Rhimes struggled to get a pilot off the ground at HBO or ABC.

Race

In tandem with discourse surrounding Girls privilege, was the conversation around the show’s racially monochromatic world, its largely absent people of colour, who, when present, were coded as working class. Dodai Stewart, editor of feminist culture blog Jezebel, which had excitedly hyped Girls, voiced her own weary disappointment, ’Girls was meant to be different from what we usually see on TV: Highly current, thoroughly modern. But the casting choices are not different.’

Earlier that season another ‘girl’ sitcom 2 Broke Girls, faced a critical drubbing over its use of regressive racial stereotypes. Whilst 2 Broke Girls was a critically maligned text, there was a squeamish response to a critically cherished one such as Girls being highlighted over diversity. The second wave of commentary came from culture websites, who targeted the same educated, liberal female demographic as Girls. Particularly the influential feminist and ladyblogs – from Jezebel to Racialicious to The Hairpin – sites whose contributors were largely more diverse than the staffs of traditional news media – and television writers rooms. They offered thoughtful, witty posts by women of colour who shared the lifestyles and backgrounds of the Girls, yet voiced their dashed hopes this ‘universal’ and ‘authentic’ representation of young women would mean they wouldn’t have to, yet again, read themselves onto white women. Jenna Wortham at The Hairpin noted that ‘the problem with Girls is that while the show reaches — and succeeds, in many ways — to show female characters that are not caricatures, it feels alienating’.

On Gawker Cord Jefferson voiced the continuing, wearing nature of this exclusion;

‘The thing that sucks about those shows is that millions of black people look at them and can relate on so many levels to Hannah Horvath and Charlotte York and George Costanza, and yet those characters never look like us. The guys begging for money look like us. The mad black chicks telling white ladies to stay away from their families look like us. Always a gangster, never a rich kid whose parents are both college professors. After a while, the disparity between our affinity for these shows and their lack of affinity towards us puts reality into stark relief: When we look at Lena Dunham and Jerry Seinfeld, we see people with whom we have a lot in common. When they look at us, they see strangers.’

In the interview with NPR’s Terri Gross Dunham spoke of the ‘accident’ of her default to white protagonists, and her fear of tokenism. Yet, as further commentaries suggested, are we really faced with either racial tokenism or nothing at all? Was the experience of women of colour so very alien to white writers? TV critics such as Mo Ryan made valuable arguments as to the institutionalised whiteness within HBO and television as a whole, yet here the wrapping of Girls so tightly around Dunham’s authorship returns to haunt critics. For if you are to celebrate Dunham’s creative freedom and choices, crediting the show strongly to her ‘voice’, you must lay these race-based choices at her door too.

I would suggest – as others have – that this conversation about Girls did valuable work in making race and in particular, whiteness visible, highlighting the cultural default to whiteness that Dunham vocalised. This wasn’t Girls, it was White Girls. In a post on Flow, Camille DeBose highlighted a key quote from Richard Dyer’s seminal book White;

“… there is something at stake in looking at, or continuing to ignore, white racial imagery. As long as race is something applied to non-white peoples, as long as white people are not racially seen and named, they/we function as a human norm… There is no more powerful position than that of being ‘just’ human. The claim to power is the claim to speak for the commonality of humanity…” (1997:1-2)

As DeBose pointed out, in naming the whiteness of Girls, these conversations problematised the claims for the Girls’ universality of female experience.

Conclusion

Arguably this conversation about authorship, class and race did mutate into something more problematic – the early thoughtful critiques of race and class were used as excuse for misogynist attacks on Lena Dunham and her crime of creating-whilst-female. Yet, these remain conversations we are having about Girls, about race and class in television, about cultural squeamishness over the display of womens bodies that do not conform to ‘ideal’ femininity or sexual roles, about female anti-heroes, about the paucity of female voices in culture and the boxes we put them in, about womens refusal, as TV critic Alyssa Rosenberg put it, to ‘stay in her assigned story’. One things for sure, we’ll never stop talking about Girls.